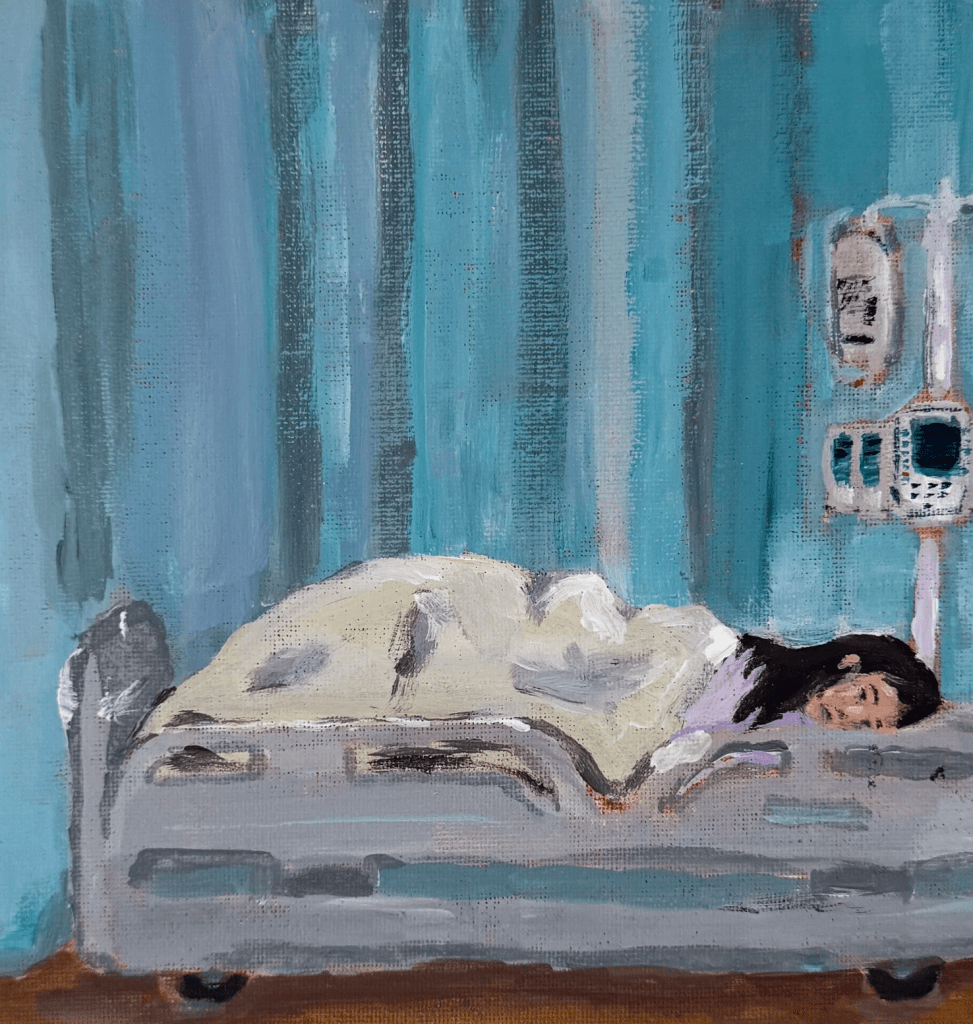

Contemplation’ reflects on the lived experiences of hospitalized patients, exploring the psychological process of navigating uncertainty during moments of solitude amid the otherwise chaotic hospital environment.” Sarah Yang, a third-year medical student at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, draws inspiration from her everyday life and hopes to integrate art into her future career as a physician.

The Color Purple

Nereida Hayes, The Color Purple, Fall 2025

When I was fifteen, I thought fatigue was just a side effect of being a student — late nights, too much homework, not enough sleep. But then the exhaustion turned into joint pain, then fevers, then a rash that wouldn’t fade. It took months, maybe a year, before the word lupus was spoken aloud in the sterile quiet of the doctor’s office.

At first, I didn’t even know what it meant. All I heard was chronic, incurable, lifelong. Words that sounded like locks clicking shut. I remember sitting in the passenger seat on the drive home, staring out the window, and feeling as if the world had pulled away from me, as if everyone else was still sprinting forward while I was stuck behind glass.

Depression crept in quietly. It wasn’t just sadness; it was the feeling that I’d lost who I was supposed to be. My body felt foreign, unpredictable. Some days I woke up swollen and aching, others I couldn’t even lift my backpack. Friends stopped asking me to hang out after school, not out of cruelty, but because they didn’t know what to say. I didn’t either.

There were nights when I cried into my pillow until it was damp, wondering if my life would ever feel normal again. My mom would sit beside me, brushing my hair away from my face, reminding me that lupus didn’t define me. I wanted to believe her, but I couldn’t see past the fog of appointments, pills, and the constant waiting for test results.

Then one afternoon, during a hospital stay, a nurse asked if I wanted to join the art therapy group down the hall. I almost said no. But something in her voice — gentle, certain — made me nod. That day, I painted for the first time in years. I chose the color purple, the symbol of lupus awareness, and filled the page with messy streaks and soft edges. Somehow, the pain in my wrists eased as the brush moved.

That was when I began to make peace with my illness. Not by giving up, but by realizing life with lupus isn’t about returning to who I was—it’s about learning to love who I’m becoming.

I still grieve the old me, the one who moved without limits, but grief has softened into acceptance. I’ve found beauty in slower mornings, in quiet strength, in the courage to keep sharing my story.

Lupus remains—sometimes loud, sometimes quiet, but I remain too, still creating, still learning, still finding color between pain and peace.

Can Stories Heal?

An essay by Aimee Schlemmer, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Ron Capps, a 25-year Army Veteran who served in Afghanistan, Iraq, Rwanda, Darfur, and Kosovo, left the military in 2008 carrying deep psychological wounds. Traditional treatments including therapy, medication, and alcohol—offered little relief. He later reflected, I came frighteningly close to taking my own life. Someone intervened, and I survived. Writing was what eventually helped me regain control of my thoughts.

After completing an MA in writing at Johns Hopkins University, Capps created the Veterans Writing Project (VWP) in 2011, a Washington D.C.–based nonprofit dedicated to supporting Veterans through storytelling. His mission is simple: provide free workshops so service members, Veterans, and their families can articulate the experiences they’ve carried in silence for years. There are so many untold stories, he explains.

Capps’ own recovery and the progress of many Veterans who participate in VWP programs demonstrates the restorative potential of writing. I wrote myself out of a very dark place. Writing lets us shape traumatic memories instead of being shaped by them.

At Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Capps and colleague Dario DiBattista lead weekly creative writing sessions for Veterans coping with PTSD and traumatic brain injuries. DiBattista frames their work simply: Writing helped us, and maybe it can help you too. He says that repeatedly telling one’s story gradually changes its grip: the more it’s expressed, the less overwhelming it becomes.

Working primarily with special operations Veterans, individuals accustomed to unconventional problem-solving, Capps and DiBattista find that participants are often willing to try writing as part of their healing. Many describe a sense of relief after putting their story into words for the first time. Those who continue writing often notice they sleep better and seek medical care less frequently. DiBattista believes this is because all therapy ultimately involves expressing one’s experience—writing is simply another, highly effective avenue.

And the impact extends beyond the writers themselves. When others read Veterans’ stories, it fosters understanding, challenges assumptions, and deepens empathy. As DiBattista notes, such writing can offer readers new perspectives, new ways of thinking, and a compassion they might not have had before.

Storytelling has served as a form of healing for centuries, and figures like Ron Capps are helping reintroduce it into modern health care through what is now known as narrative medicine. Neurologist and psychiatrist Jonathan Shay—another pioneer in this field—observes that some healing practices are only now being recognized, while others must be reclaimed from the wisdom of past cultures.

For more than three decades, Shay has listened to Veterans describe the psychological wounds of combat at the Boston-area Veterans Affairs Outpatient Clinic. His influential book Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character draws parallels between Homer’s Iliad and the experiences of contemporary soldiers, revealing how ancient literature can illuminate truths that often remain unspoken in clinical settings. Shay argues that storytelling is vital to recovery because it allows individuals to voice their experiences honestly, express emotion, and form meaningful connections with others.

He maintains that effective care for combat Veterans must be rooted in moral and social support rather than solely medical intervention. True healing, he explains, occurs when survivors regain agency and share their trauma within a supportive community. Healing is done by survivors, not to survivors. This philosophy lies at the heart of narrative medicine’s approach to care.